This is me-- trapped inside one of Andy Warhol's Mao prints.

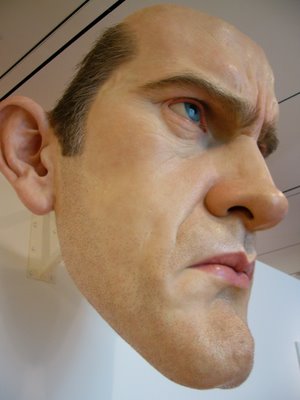

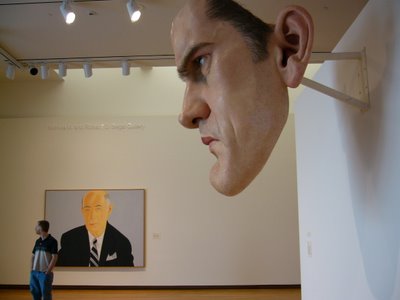

Look over my shoulder and see a floating mask.

That's an eight foot tall self-portrait by sculptor Ron Mueck, who has done a lot of work for films, including Labyrinth.

I'm in the Duke University museum here, which rotates a large collection through a small exhibition space. The collection is world class, and the building is a neat balance of opposites: open yet intriguing, austere but exciting. It's a recent design (2005) by this cool guy, who did our own Kimmel Center.

The Mao prints are some of my favorite Warhols. Why is Andy Warhol's stuff always so much better and more exciting in person? They are simple, flat iconic graphics, which should work just as well in a book or on the web. So why are they more powerful live? Is it the scale?

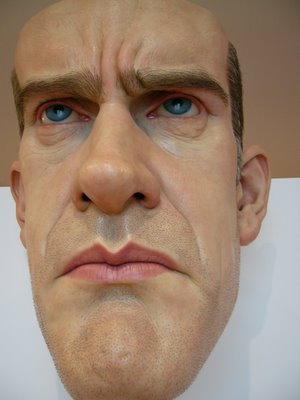

Here are some clearer pictures of the Mueck mask-- domineering, funny, and powerful.

The Nasher Museum had arranged its current selection from the larger collection around the theme of gender-- With Mao, Mueck's mask, and the tidy suited fellow above, they started the exhibit with some strong statements of modern masculinity. In the ancient and medieval areas there were interesting Christs, plus some stone apostles, and Samson and Heracles. I guess I had forgotten about the theme of the exhibit as I looked at the objects-- yet the objects did cause me to meditate on masculine identities in different cultures and times. What does it all mean? Who are we, as men? Heracles was a renowned macho hero-- the ultimate type of the powerful man in both ancient and modern worlds--and had several male lovers. Christ the savior becomes the moral ideal for the West, not by kicking ass, but by conquering through non-violence. Both of these icons, these powerful symbols-- of masculine strength and enlightened moral and spiritual leadership--are husks to us now, resonant names with little content. Our civilization is rooted in Greek and Roman, Jewish and Christian ideas. Yet we have no place in our pantheon of archetypes for gay jocks, bisexual warriors, or leaders who win by peaceful means, and teach by listening. These personas could be useful touchstones for us, and they are legitimately a part of our heritage--our "patrimony." How was value leached from them? How did they become degraded through time? How did we inherit, from a rich and useful past, weary, stale, flat and unprofitable notions of manhood?

Looking at some of this art I became angry, thinking of how we have silenced history

tortured nature

and consigned our nobler possibilities to eternal stress positions.